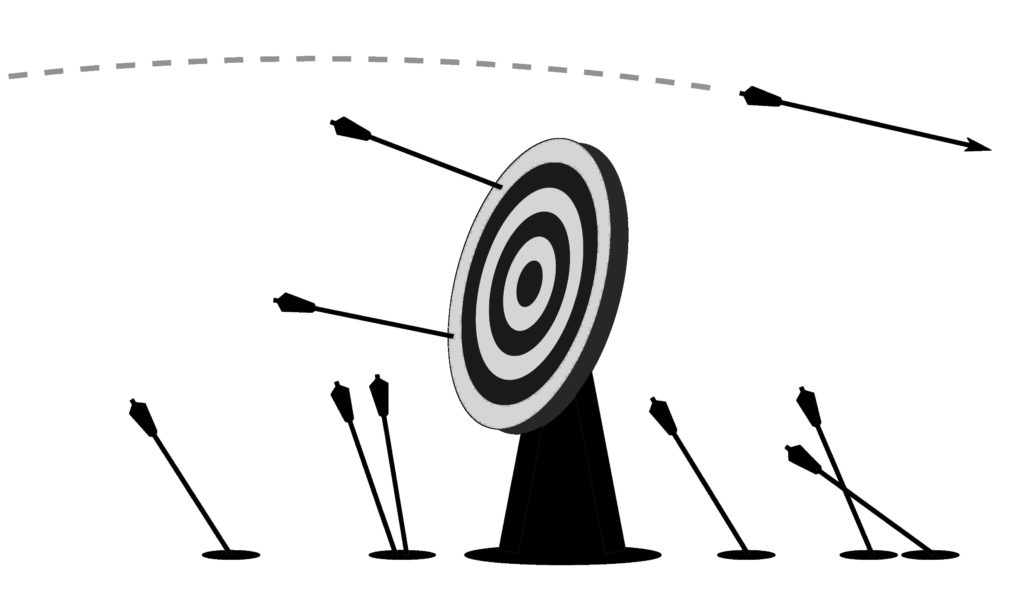

Well, you might be machine learning the wrong thing…

Well, you might be machine learning the wrong thing…

Because it’s easy to get complacent. You find something familiar, set it as a goal, work hard to achieve it, and get distracted from true success.

This is particularly true for machine learning people, because we have so many incredible tools for measuring the quality of the models we produce. It’s great. A classification task? Precision and a recall. You move those numbers in the right direction and you’re achieving success. Move them further, you’re doing better. You have the game set up. You have the tools. You can win!

Sometimes that works, but get tunnel vision on optimizing your models — before long you’ll be machine-learning the wrong thing.

For example, consider a system to stop phishing attacks.

Phishing involves web sites that look like legitimate banking sites but are actually fake sites, controlled by abusers. Users are lured to these phishing sites and tricked into giving their banking passwords to criminals. Not good.

But machine learning can help!

Talk to a machine-learning person and it won’t take long to get them excited. ML people will quickly see how to build models that examine web pages and predict whether they are phishing pages or not. These models will consider things like the text, the links, the forms, and the images on the web pages. If the model thinks a page is a phish, block it. If a page is blocked, a user won’t browse to it, won’t type their banking password into it. Perfect.

So number of phishing pages you block seems like a great thing to optimize — block more phishing sites, and the system is doing a better job.

Or is it?

What if your model is so effective at blocking sites that phishers quit? Every single phisher in the world gives up and finds something better to do with their time? Perfect! But then there wouldn’t be any more phishing sites and the number of blocks would drop to zero. The system has achieved total success, but the metric indicates total failure. Not great.

Or what if the system blocks one million phishing sites per day, every day, but the phishers just don’t care? Every time the system blocks a site, the phishers simply make another site. Your machine learning is blocking millions of things, everyone on the team is happy, and everyone feels like they are helping people—but the number of users losing their credentials to abusers is the same as before your system was built. Not great.

And these are sort of toy examples, but there are two important points: Things change and your metrics aren’t right.

Things change

Your problem will change, your users will change, the business environment will change. If you don’t also change your machine learning goals – you’ll be machine-learning the wrong thing in no time.

Some common sources of change include:

- Users – new users come, old users leave, users change their behavior, users learn to use the system better, users get bored.

- Problems – your problem changes, new news stories are published, fashion trends changes, natural disasters occur, elections happen.

- Costs – the cost of running your system might change, which puts new constraints on model execution and data and telemetry collection.

- Objectives – the business environment might change, maybe a feature that attracted users last year is ho-hum this year.

- Abuse – if people can make a buck by abusing your system, you can bet they will…

If you aren’t thinking about how these types of change are affecting your system on a regular basis, you’re machine-learning the wrong thing.

Your Metrics Aren’t Right

The true objective of your system isn’t to have high-quality intelligence. The true objective is something else, like keeping users from losing their passwords to abusers (or maybe even making your business some money).

A system’s true objective tends to be very abstract (like making money next quarter), but the things a system can directly affect tend to be very concrete (like deciding whether to block a web site or not). Finding a clear connection between the abstract and concrete is a key source of tension in setting goals for machine learning and Intelligent Systems. And it is really hard.

One reason it is hard is that different participants will care about different types of goals (and have their own tools for measuring them). For example:

- Some participants will care about making money and attracting and engaging customers.

- Some participants will care about helping users get good outcomes.

- Some participants will care that the intelligence of the system is accurate.

These are all important goals, and they are related, but the connection between them is indirect: you won’t make much money if the system is always doing the wrong thing; but making the intelligence 1% better will not translate into 1% more profit.

If you don’t understand how your metrics relate to true success, you’re machine learning the wrong thing (Ok, Ok… I promise, I’ll only say it one more time…)

Machine learning the right thing…

So you’ll need to invest in keeping your goals healthy.

Start by defining success on different levels of abstraction and coming up with some story about how success at one layer contributes to the others. This doesn’t have to be a precise technical endeavor, like a mathematical equation, but it should be an honest attempt at telling a story that all participants can get behind.

Then meet with team members on a regular basis to talk about the various goals and their relationships. Look at some data to see if your stories about how your goals relate might be right – or how you can improve them. Don’t get too upset that things don’t line up perfectly, because they won’t.

For example:

- On an hourly or daily basis: optimize model properties, like the false positive rate or the false negative rate of the model. For example: how many phishing sites are getting blocked?

- On a weekly basis: review the user outcomes and make sure changes in model properties are affecting user outcomes as expected. For example: you blocked more phishing sites, did fewer users end up getting phished?

- On a monthly basis: review the leading indicators – like customer sentiment and engagement – and make sure nothing has gone off the rails. For example: How many users say they feel safer using your browser because of the phishing protection? How many are irritated by it?

- On a quarterly basis: look at the organizational objectives and make sure your work is moving in the right direction to affect them. For example: market share, particularly for visits to banking sites?

Your team members will make better decisions when they have some understanding of these different measures of success, and some intuition about how they relate.

And remember: you’ll need to revisit the goals of your Intelligent System often. Because things change, and if you don’t invest the time to keep your goals healthy – you’re machine learning the wrong thing!

You can learn much more in the book: building intelligent systems. You can even get the audio book version for free by creating a trial account at Audible.

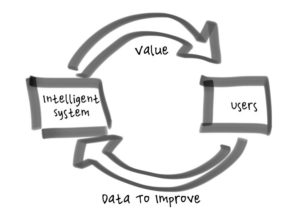

Closing the loop is about creating a virtuous cycle between the intelligence of a system and the usage of the system. As the intelligence gets better, users get more benefit from the system (and presumably use it more) and as more users use the system, they generate more data to make the intelligence better.

Closing the loop is about creating a virtuous cycle between the intelligence of a system and the usage of the system. As the intelligence gets better, users get more benefit from the system (and presumably use it more) and as more users use the system, they generate more data to make the intelligence better. Intelligent Systems make mistakes. There is no way around it. The mistakes will be inconvenient, some will be actually quite bad. If left unmitigated the mistakes can make an Intelligent System seem stupid, they could even render an Intelligent System useless or dangerous.

Intelligent Systems make mistakes. There is no way around it. The mistakes will be inconvenient, some will be actually quite bad. If left unmitigated the mistakes can make an Intelligent System seem stupid, they could even render an Intelligent System useless or dangerous. In my decade of managing applied machine learning teams I’ve interviewed maybe a hundred people. Over that time, I’ve come to rely on two main questions. I’m going to tell you what they are.

In my decade of managing applied machine learning teams I’ve interviewed maybe a hundred people. Over that time, I’ve come to rely on two main questions. I’m going to tell you what they are.